Changing perspectives: testing an ageism intervention (Human Rights Commission)

Link to this Human Rights Commission story.

Overview

The Commission’s research aimed to contribute to a greater understanding of how negative perceptions of ageing and older adults may be shifted. The Commission set out to evaluate the effectiveness of a brief, one-off educational intervention in reducing ageist attitudes among workers in aged care and community settings.

Surveys were conducted pre-workshop and at two follow-up points: immediately after the workshop and 2–3 months post-workshop. The age awareness survey was a single 2.5-hour interactive session that covered topics including common assumptions about ageism and older adults, and what we can do to reduce ageism. A total of 329 aged care and community workers participated in the research by doing at least one survey.

The results provide support for a brief, targeted intervention to drive positive changes in attitudes and behaviour that may be sustained over time.

How common is ageism?

Ageism is a serious problem. The World Health Organisation’s 2021 Global Report on Ageism found that one in two people worldwide are ageist, and called ageism ‘prevalent, ubiquitous, and insidious’. It’s also widespread in Australia. The Australian Human Rights Commission’s 2021 What’s age got to do with it? report found that 90% of adults agree ageism exists in Australia, 83% consider it to be a problem, and 65% believe it affects people of all ages.

Ageism – particularly against older adults – is so deeply ingrained in our societal norms and values that it can be difficult to recognise within ourselves and our surroundings. For example, ageist language is often hidden behind humour and good intentions, and used without any intent or awareness of implicit bias against older adults.

Ageism can have serious consequences for older people’s health and wellbeing. Studies have consistently shown links between ageism and adverse health outcomes such as shorter lifespan, reduced quality of life and wellbeing, physical and mental health conditions, and cognitive impairment.

Key findings

A brief, one-off educational intervention can be a powerful tool in creating positive changes in attitudes and behaviours towards older people that may last over time.

We found statistically significant reductions in ageist attitudes and improvements in ageing expectations upon completion of the workshop, and these improvements remained at follow-up 2–3 months later.

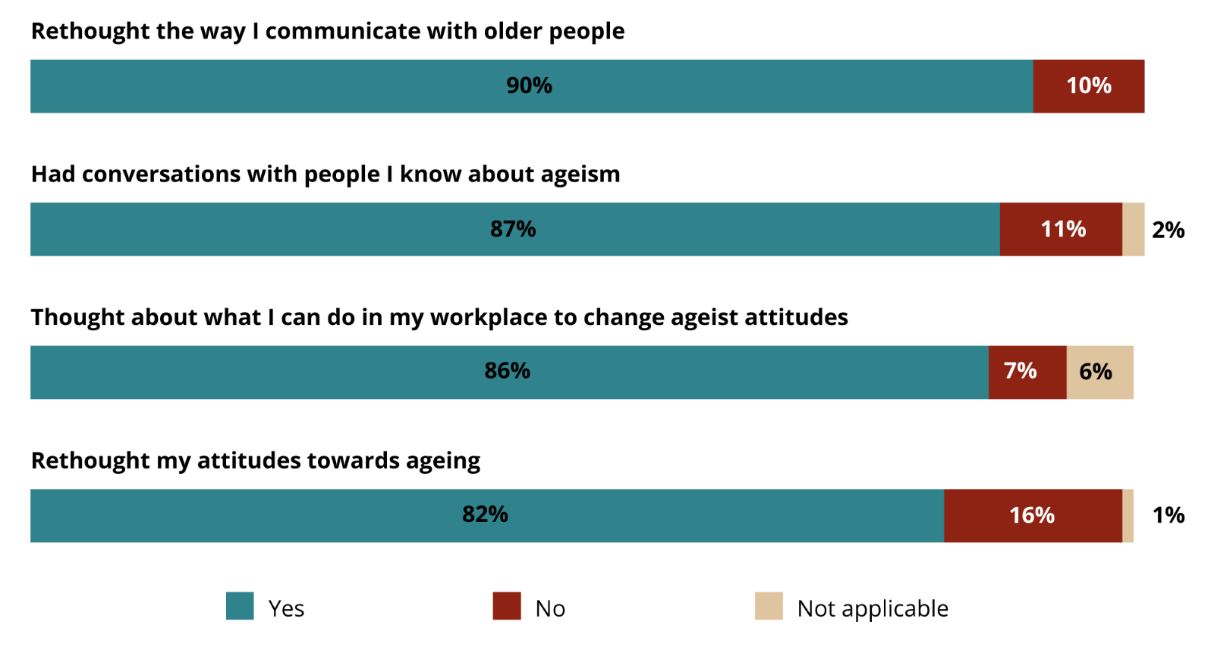

These were the results in the follow-up survey:

Post-workshop focus groups provided further examples of specific changes that occurred as a result of the workshop, including:

- Avoiding making assumptions about people based on age.

- Changing the language they use – e.g., not using elderspeak, not making unnecessary references to someone’s age.

- Being more collaborative in their interactions with older clients.

- Respecting clients’ autonomy and independence.

- Seeing and treating each older person as an individual, focusing on people’s capabilities, rather than their limitations.